Nutrition

The Ultimate Guide to Intermittent Fasting (Can It Help With Weight Loss?)

Fasting is one of the oldest known treatments for disease. It’s used to treat a huge range of health issues, including improving insulin resistance, weight loss, cognitive issues, and even reversing aging itself.

But one specific type of fasting is currently very fashionable, and it seems like everyone’s talking about it. It’s called intermittent fasting (IF for short). However, despite the hype, intermittent fasting isn’t for everyone. In fact, it can hurt you if done incorrectly.

In this article, we’re going to look at how to do intermittent fasting properly to gain the potential benefits and avoid the risks. As you’ll soon learn, everyone’s biology is different and understanding this is the key to your success.

TL;DR: This article covers the science and answers some of the most frequently asked questions about intermittent fasting. We also share an infographic with the different fasting schedules you can follow. Also, find out why the keto diet + intermittent fasting is a great approach. Pro tip: our Intelligent Keto ebook contains tasty recipes that can help you reach your weight loss goals faster.

Table of Contents

Are you fasting or starving? How to start intermittent fasting?

The first rule of intermittent fasting is the most important, and that is don’t starve yourself!

At any given time, the human body is using both glucose and fat to make energy. In fact, at rest, around 50% – 70% of the energy we need comes from fat (1). However, we always need glucose available. The red blood cells (RBC) that carry oxygen around the body cannot use fat to make energy, only glucose.

Also, glucose is vital for the brain to run. The brain can use ketones, a fat-based molecule, for energy. But even where’s a large supply of ketones available, the brain still needs at least 33% of its energy to come from glucose (2).

We need sugar in our blood at all times!

Sugar fuels our RBCs and our brain. On average, there are 4g (0.14 oz) of sugar circulating in the bloodstream. 60% of this is used by the brain for energy (3). The body will go to great lengths to keep this 4g stable. If it goes too low, our metabolic functions start to go wrong. If it continues to drop, it can lead to seizures and even death.

During our evolution, blood sugar drops were a bigger risk factor than having high levels. In other words, starvation was more likely than our chance of finding boxes full of donuts to feast on.

Because of this, we have four hormones that can raise blood sugar:

- glucagon

- adrenaline

- cortisol

- growth hormone

However, we have only one to lower it — insulin.

What are the most common intermittent fasting methods?

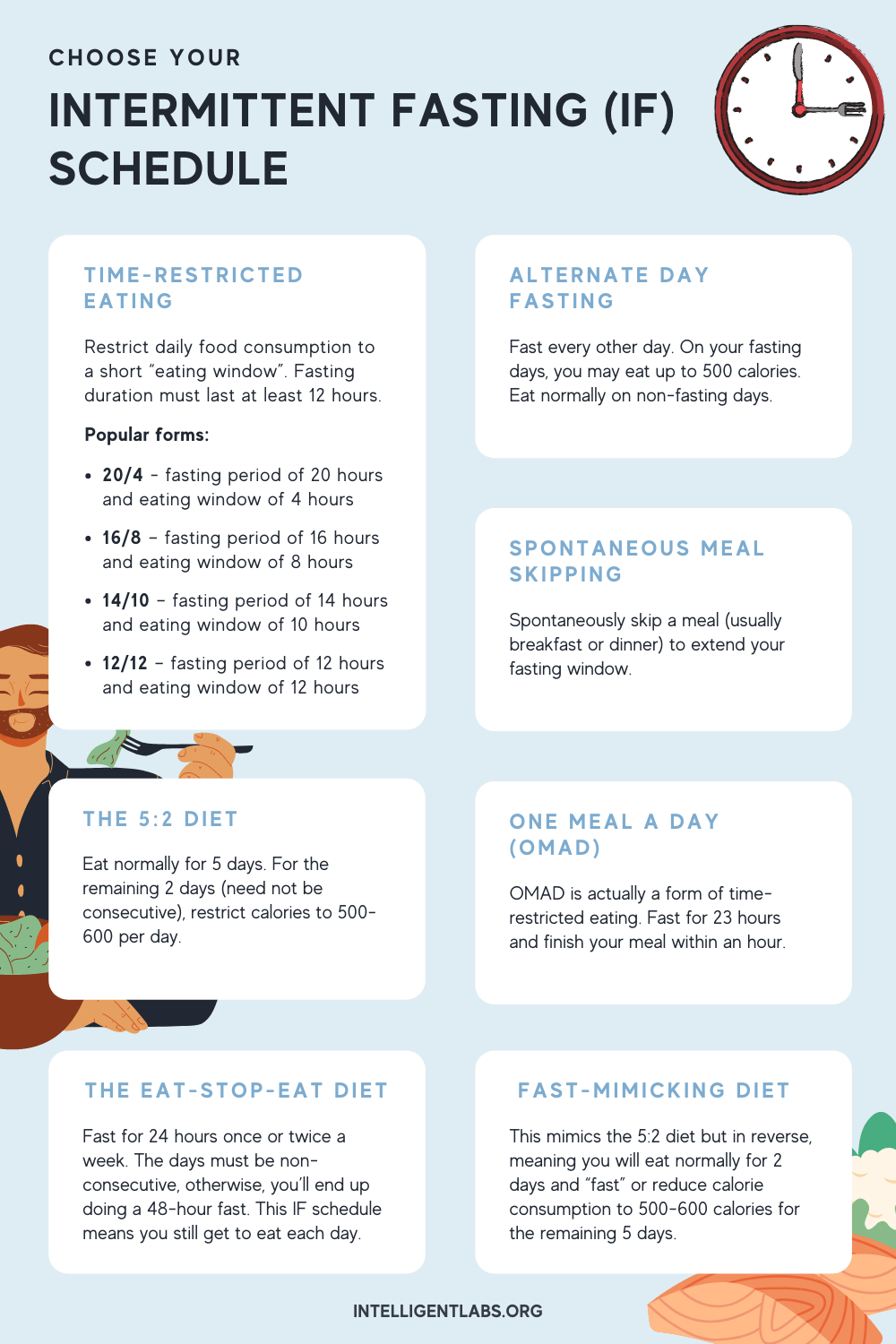

Once you know you are fat / keto-adapted, I recommend the 16:8 method. This means fasting for 16 hours each day. Your eating window is 8 hours. The 16-hour fast benefits may include helping with weight loss, heart disease, diabetes, blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and the reduction of inflammation (4).

There are other intermittent fasting methods that are commonly used include the following:

The 5:2 diet involves eating normally 5 days of the week while restricting your calorie intake to 500–600 for 2 days of the week.

The alternate-day fasting involves eating normally on one day and restricting your calorie intake to 500–600 every other day.

If these work better for you, then that is fine, the health benefits will still be similar. However, I find that 16:8 method is easier to maintain over the long term and fits in with people’s social lives.

Check out the infographic below for other intermittent fasting schedules:

What’s the role of the liver in fasting?

Here’s a hint: it keeps your blood sugar stable.

When the brain senses a drop in blood sugar levels, it signals for the production of the 4 hormones – glucagon, adrenaline, cortisol, and growth hormone. This, in turn, signals the liver and blood sugar is increased (5).

The liver does this in two ways:

The first is by releasing glycogen from its glycogen stores (glycogen is simply the name for stored glucose in the body).

The second way is through the production of more glucose in a process called gluconeogenesis. The liver stores about 80-100 grams of glycogen. Relatively, this is a huge amount and equals roughly 5%-6% of the liver’s weight (compared to 1%-2% in muscle) (6).

Whilst the liver keeps blood sugar stable, the body also starts to get more energy from fat. It does this by increasing the breakdown of fat cells (adipocytes) to release fatty acids into the blood. This increases the burning of the fatty acids for energy in a process called beta-oxidation.

At the same time, more of the fatty acids arrive at the liver from the bloodstream. These are used to produce more ketones.

What’s the role of ketones in fasting?

The increase in ketone production during periods of fasting helped our ancestors survive periods when food was not freely available. Ketones give us another source of energy so we could prioritize glucose stores for the brain and RBCs (7).

Unfortunately, fatty acids can only be used by the brain in very small amounts (8). However, the brain loves ketones, so producing and using ketones allows us to spare glucose. It gives the brain a good energy source, so it doesn’t panic and flood the body with stress hormones.

Who should do intermittent fasting?

The problem is not everyone produces ketones efficiently. Studies have shown that people who are physically fit and train regularly have higher levels of ketones. They also have a better ability to use those ketones to produce energy (9, 10).

Also, these individuals can much more easily break down stored fat into free fatty acids. This gives the liver access to a larger amount of fat, allowing it to produce more ketones. Fit individuals can also better use ordinary fatty acids to produce energy as well (through beta oxidation).

This means that some people will find it relatively easy to fast. And they’ll be able to easily switch to a higher level of fat burning, as well as ketone synthesis and use.

Who should NOT do intermittent fasting?

People who are overweight, untrained, or have other health issues may struggle with intermittent fasting. A good way to picture the problem is that fasting is basically stressing the body.

For healthier people, this is a stress they can handle, and it’s this healthy stress that produces the positive potential benefits of fasting (11, 12).

Stressing cells, healthy cells at least, creates a positive response making the cells ‘stronger’ and more able to resist stress in the future. It works in the same way that physical training makes someone stronger, faster, or builds greater endurance.

Stress that doesn’t cause a positive response causes damage.

People who try intermittent fasting need to have the metabolic flexibility to be able to switch between using more glucose and using more fat for energy.

This flexibility is vital, and I often cringe when I hear fit and healthy nutritionists or personal trainers recommending intermittent fasting to their clients without considering their metabolic flexibility.

So how do I know if I can handle intermittent fasting?

There are two warning signs that you can’t handle intermittent fasting.

Warning sign #1: The first one is rapid weight loss

Now that might sound a bit strange because surely one of the benefits of fasting is weight loss. It is, but only if the weight lost is fat.

If you are starving yourself, your body will use all of its glycogen supplies for energy. Whilst the liver only has 80-100 grams of glycogen stores, we also keep glycogen in other parts of the body. The biggest storage is in the muscles, but it’s also in other parts of the body, even the brain!

On average, people have around 600 grams of glycogen stored throughout the body, although it can go up to 1kg. For every 1 gram of glycogen we burn for energy, we also lose another 3-4 grams of water with it (13).

So using up 600 grams of glycogen could mean an extra 2400 grams of water lost. This means 3kg in total weight could be lost very quickly and none of it would be fat.

We can also break down protein for energy, with the biggest source being our skeletal muscle. For every gram of muscle protein broken down, we also lose another 4 grams in water weight (14). So people can easily see significant weight loss without any of it being fat.

Warning sign #2: Intermittent fasting shouldn’t be a struggle

I feel like I’m dying, but I’m losing weight!

The second thing is that you feel bad. Intermittent fasting should NOT be a struggle.

Low blood sugar raises hormones associated with stress. When glycogen levels at the liver also start to decrease, the brain will further increase hormone levels. The exception is when it’s getting an adequate supply of ketones for fuel to take over from the lack of glucose.

However, when it doesn’t have an adequate supply of ketones, then it will increase stress hormone levels and create a whole range of negative side effects (15).

That’s when people experience intermittent fasting side effects, which may include:

- hunger cravings

- lightheadedness

- dizziness

- anger

- weakness

- irritability

- anxiousness

- depressive feelings, or anything similar.

So if you feel bad and have rapidly lost lots of weight — STOP.

When you are starving, motivation can only take you so far. Eventually, it will fail. When that happens, people very often have rebound weight gain. This is because they haven’t actually burnt any fat, just muscle, and glycogen. Your brain also now believes there is a shortage of food. So when you finally give in and start eating again, you will have a huge appetite.

Also, your body will quickly rebuild glycogen stores to even greater levels than before. It will store any excess calories as fat as a safety measure in case food becomes scarce again (16). You, therefore, end up with more fat and glycogen than before you started with and you gain weight as a result.

So if I feel bad I shouldn’t do intermittent fasting at all?

No, you can still fast, but you need to do a fat adaption program first. This means training your body to get better at breaking down fat and using it directly for energy and for producing ketones. It’s the same program that people who are starting a ketogenic diet do and lasts about 3 weeks. After doing this, your body will be producing adequate ketones to fuel your brain throughout the fasting periods.

I have covered it in depth in this article on the ketogenic diet, so please read it if you need to. However, a summary of the steps that need to be taken are:

- Start off eating 75% – 80% of calories coming from fat, 5% of calories coming from carbs, 15% – 20% of calories coming from protein.

- Measure your ketone levels, using an electronic ketone meter (available online). You are trying to get to a blood ketone level of 0.5mmol – 3mmol, which is known as nutritional ketosis.

- Take the supplements C8 oil and/or BHB ketones if you are not in nutritional ketosis of 0.5mmol – 3mmol to give your brain fuel as you become keto-adapted.

- If you are still not in nutritional ketosis, increase fat and reduce carbs and/or protein.

- When you are in nutritional ketosis, continue there for 3 weeks. After 3 weeks, you are ‘keto adapted’ and can safely try intermittent fasting again.

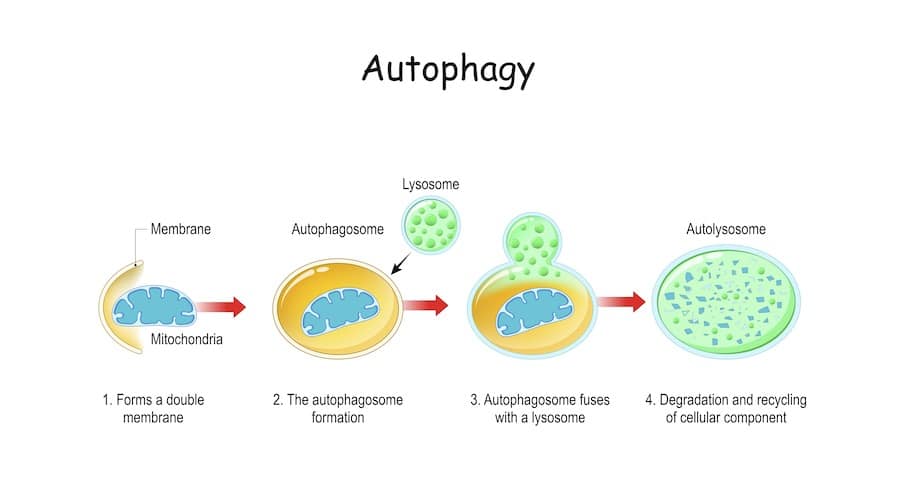

Intermittent fasting and autophagy

Many of the benefits of intermittent fasting are caused by a cellular process called autophagy. This is a process where the body reuses and ‘recycles’ old and damaged cell parts.

It’s a little bit like fixing your house up after one too many wild parties. If we are eating all the time, then it’s like a party for our cells. But fasting allows the opposite to happen, where we replace, repair, and renew any damage.

Autophagy starts to happen in our bodies about 12 hours after our last meal. So the 16:8 intermittent fasting hours are a good method for increasing autophagy (17).

Related article: Breaking Down The Science Of Autophagy – Beyond Popular Fasting Diets

Intermittent fasting and working out

Exercising while fasting can increase autophagy, and some people following the 16:8 method like to add this to their routine (18). Whilst this can bring added benefits, people who want to try it need to be aware that the extra energy burnt during a workout could limit the availability of ketones for the brain.

In other words, you shouldn’t notice any negative side effects when you workout fasted, beyond the normal feelings you would get from the workout itself. If you find you are experiencing negative side effects when exercising, don’t try and push through. Instead, ease back on exercise intensity to a load where there are no side effects. Then if you want to, you can slowly build up the intensity.

Can children and teens try intermittent fasting?

I don’t recommend fasting for kids or teens going through puberty, as they have elevated nutritional and caloric requirements (19). Also, a study on kids aged 9-11 found that skipping breakfast had negative effects on their late-morning problem-solving performance (20).

Conclusion

Intermittent fasting can produce definite health benefits and can be used in the short term, or over the longer term safely. However, it is important to make sure it is being done properly, and that anyone trying the diet has developed the metabolic flexibility to switch between glucose and fat / ketone use.

When people take the time to adapt properly, fasting can produce really good health benefits. Once fully adapted, participants can also choose to fast just for a few days a week, instead of every day, depending on their lifestyles.

References

(1) Carnitine transport and fatty acid oxidation, Nicola Longo, Marta Frigeni, Marzia Pasquali, Biochim Biophys Acta . 2016 Oct;1863(10):2422-35.

(2) Biochemistry, Ketone Metabolism, Caleb B. Cantrell; Shamim S. Mohiuddin. StatPearls [Internet].

(3) Four grams of glucose, David H Wasserman, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab . 2009 Jan;296(1):E11-21.

(4) Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men With Overweight and Obesity: The TREAT Randomized Clinical Trial, Dylan A Lowe, Nancy Wu, Linnea Rohdin-Bibby, A Holliston Moore, JAMA Intern Med . 2020 Nov 1;180(11):1491-1499.

(5) Some hormonal influences on glucose and ketone body metabolism in normal human subjects, D G Johnston, A Pernet, A McCulloch, G Blesa-Malpica, J M Burrin, K G Alberti, Ciba Found Symp . 1982;87:168-91.

(6) Fundamentals of glycogen metabolism for coaches and athletes, Bob Murray and Christine Rosenbloom, Nutr Rev. 2018 Apr; 76(4): 243–259.

(7) Postexercise muscle glycogen resynthesis in humans, Louise M Burke, Luc J C van Loon, John A Hawley, J Appl Physiol (1985) . 2017 May 1;122(5):1055-1067.

(8) Why does brain metabolism not favor burning of fatty acids to provide energy? – Reflections on disadvantages of the use of free fatty acids as fuel for brain, Peter Schönfeld, and Georg Reiser, J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013 Oct; 33(10): 1493–1499.

(9) Fatty acid and ketone body metabolism in the rat: response to diet and exercise, E W Askew, G L Dohm, R L Huston, J Nutr . 1975 Nov;105(11):1422-32.

(10) POST-EXERCISE KETOSIS R.H. Johnson J.L. Walton H.A. Krebs D.H. Williamson, Published:December 27, 1969

(11) Dietary restriction and 2-deoxyglucose administration improve behavioral outcome and reduce degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in models of Parkinson’s disease, W Duan, M P Mattson, J Neurosci Res . 1999 Jul 15;57(2):195-206.

(12) Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting and caloric restriction on the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems, Mark P Mattson, Ruiqian Wan, J Nutr Biochem . 2005 Mar;16(3):129-37.

(13) Glycogen storage: illusions of easy weight loss, excessive weight regain, and distortions in estimates of body composition, S N Kreitzman, A Y Coxon, K F Szaz, Am J Clin Nutr . 1992 Jul;56(1 Suppl):292S-293S

(14) Textbook of Medical Physiology, 5th edition. Arthur C. Guyton Robert S. Alexander Ph.D, The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Volume 17, Issue 4 p. 260-260

(15) Effects of a 48-h fast on heart rate variability and cortisol levels in healthy female subjects, N Mazurak, A Günther, F S Grau, E R Muth, M Pustovoyt, S C Bischoff, S Zipfel & P Enck, Published: 13 February 2013

(16) Intermittent Fasting in Cardiovascular Disorders—An Overview Bartosz Malinowski, Klaudia Zalewska, Anna Węsierska, Maya M. Sokołowska, Maciej Socha, Grzegorz Liczner, Katarzyna Pawlak-Osińska and Michał Wiciński, Published online 2019 Mar 20.

(17) Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting, Stephen D Anton, Keelin Moehl… Obesity (Silver Spring) . 2018 Feb;26(2):254-268.

(18) Exercise and exercise training‐induced increase in autophagy markers in human skeletal muscle, Nina Brandt, Thomas P. Gunnarsson, Physiol Rep. 2018 Apr; 6(7): e13651.

(19) Nutrition for the Next Generation: Older Children and Adolescents, Jai K Das, Zohra S Lassi, Zahra Hoodbhoy, Rehana A Salam, Ann Nutr Metab . 2018;72 Suppl 3:56-64.

(20) Fasting and cognitive function, E Pollitt, N L Lewis, C Garza, R J Shulman, J Psychiatr Res . 1982;17(2):169-74.