Intermittent fasting is a popular diet, with millions of people jumping on the trend. Whether they were doing 16:8, 5:2, or just fasting on workdays, regular folks and celebrities alike flooded social media with their success stories.

But have you ever wondered what happens in your body when you’re doing intermittent fasting? Do you know the science behind autophagy and fasting? Scroll down as I break down the science of autophagy and intermittent fasting.

Table of Contents

What Is Autophagy?

Autophagy comes from the words ‘auto’ and ‘phagy’. ‘Auto’ means self, ‘phagy’ means eat. Combined together, autophagy literally means ‘self-eating. It is a form of self-cannibalization but NOT in a bad way.

Autophagy is the body’s natural way of cleaning out dead, damaged, and cellular organelles and other components. The whole ‘cleaning’ process helps the body regenerate new and healthy cells.

How is Autophagy pronounced?

It’s pronounced aa·taa·fuh·jee.

Why are fasting diets so popular nowadays?

Here are some of the most common reasons people do fasting diets:

1) Fasting may lead to weight loss

Many people decide to try fasting for its weight loss benefits. Studies have shown that, on average, subjects lose between 2.5% and 9.9% of their body weight during the 3-6 month period that fasting studies run for (1, 2). This weight loss is from fat mass, not muscle mass.

2) Fasting may help regulate glucose and insulin levels

Intermittent fasting may also decrease fasting glucose and insulin levels in diabetics, obese people, and non-obese individuals (3, 4).

In addition, a study on young overweight women found decreases in total and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood pressure. They also found a reduction in the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein and the hormone leptin which usually climbs higher with obesity.

On a side note, our Berberine and Ultra Pure Omega-3 supplements may also help improve glucose levels and insulin sensitivity.

3) Fasting may help with testosterone regulation

They also found an increase in SHBG (sex hormone-binding globulin), which helps to reduce the effects of testosterone. However, when testosterone climbs too high in women, it can have unwanted side effects (5).

4) Intermittent fasting may even have anti-aging effects

Most of the studies on intermittent fasting and aging are conducted on animals. The reason is simple – it’s very difficult to conduct these studies on humans. You can’t follow people for a lifetime, at least not whilst ensuring they’re on the intermittent fasting protocol.

However, the stimulation of AMPK and the Sirtuins during intermittent fasting are strongly associated with increased lifespan in animals. AMPK is a special enzyme that constantly monitors energy levels. Sirtuins, on the other hand, are a family of proteins that directly stimulate autophagy.

Studies have found that intermittent fasting increases lifespan in mice and monkeys and makes it less likely for them to develop diseases associated with aging (6). One study in mice also found that the mice who fasted also avoided the decrease in muscle mass that happens during normal aging (7).

Related article: 9 Natural Ways To Slow Down The Aging Process

5) Fasting may help with energy production

Fasting also increases the levels of NAD+, the oxidised form of NADH, which is an active form of vitamin B3 (vital for energy production).

The production of energy in the mitochondria results in more NADH becoming NAD+. This increase in the NAD+ to NADH ratio stimulates the production of the Sirtuins. Sirtuin production may help with DNA repair as well as increased lifespan (8).

How does ketosis help with autophagy?

Intermittent fasting also leads to a breakdown of fat tissue, increasing the levels of free fatty acids arriving at the liver. This increases the amount of ketones produced (9).

Ketones are fat-based molecules that can produce energy very efficiently. Burning ketones for energy produce fewer free radicals, and their use reduces inflammation.

Ketones also stimulate the production of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor).

BDNF is a growth hormone for the brain and stimulates the growth of new brain cells (neurons). It also promotes new synapses, which are connections between the neurons. The more connections or synapses we have, the more we can learn and understand.

The ‘feast and famine’ cycle and why we need a balance between these two modes

Back in ancient times, humans went through the feast and famine cycle regularly. Sometimes food was plentiful, sometimes it was scarce. However, today, for most in the developed world at least, there is an abundance of calories available all the time. So, many of us no longer go through the feast and famine cycle as our ancestors did. Instead, we are always stuck in ‘feast mode.’

The problem with this is that our bodies evolved to go through both feast and famine.

When we have enough food (feast), the cells of the body can grow and reproduce. But when we don’t have enough food (famine), the body can ‘flip a metabolic switch’ (9). This helps the body focus on strengthening our cells’ response to stress.

So, during times of ‘famine’, autophagy occurs. The cells break down old and defective cellular components, renewing and regenerating them, and increasing the production of things like antioxidants. The body then uses the broken-down parts to produce new cellular components or energy.

Ideally, there needs to be a balance between feast and famine. Here’s why:

Too much feasting and damaged proteins and other cell parts can build up, leading to cells not doing their jobs properly. Then because cells make up everything in our bodies, including our organs, eventually everything else starts to go wrong as well.

Too much famine can cause a problem too, because we spend too much time breaking down our cells in repair and not providing energy.

We really need a balance of the two functions. Intermittent fasting allows us to do this because we can mimic the periods of famine and easily mix this in with some feasting.

Balancing ‘feast and famine’ with mTOR and Autophagy

The balance between feast and famine plays out in two opposing cellular processes that are both going on in our bodies at any one time. They are mTOR and Autophagy.

mTOR is an enzyme produced in our bodies. Stimulating mTOR leads to faster cell growth and protein production. Bodybuilders and other strength athletes try to stimulate mTOR as much as possible for faster muscle gains!

Autophagy is the opposite of mTOR. As you learned above, it breaks down old and damaged cells.

Because the two processes are opposites, when mTOR is stimulated, autophagy is correspondingly low. Likewise, when autophagy is stimulated, mTOR is low.

Let’s dive deeper into the science – How does Autophagy work exactly?

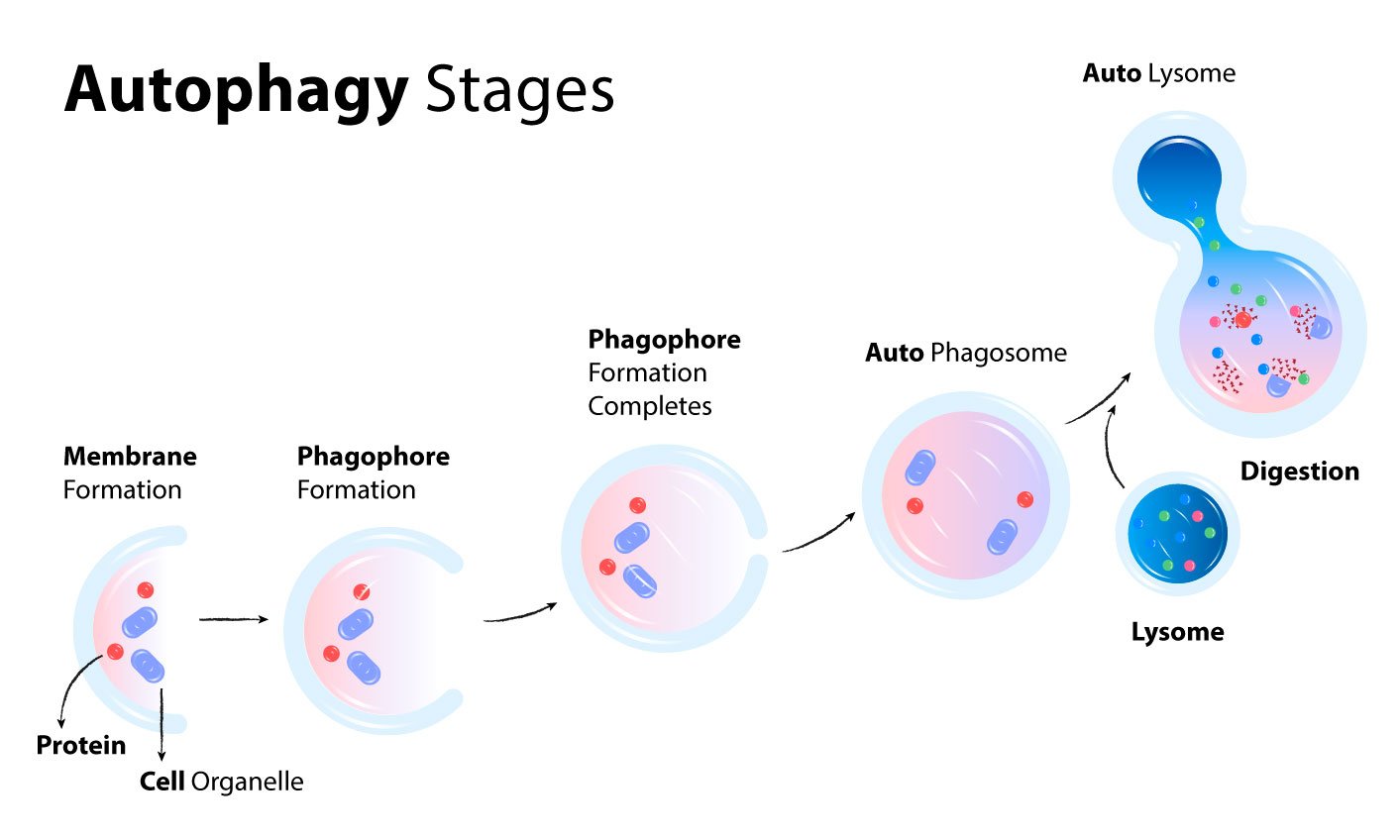

Please refer to the image below to understand how it all works:

Stage 1: Membrane formation

In autophagy, cells form special structures called phagophores. Phagophores are membranes that slowly grow to create a ball shape covered in a membrane.

The membrane is made of something called a lipid bilayer. Lipids are fat-based molecules. Lipid bilayers surround all of the organelles in our cells and all of our cells as well, all 20 billion of them!

Cell organelles perform different functions in our cells. You can maybe compare them to different organs in our body.

Stage 2: Phagophore formation

Whilst the ball or phagophore is fully forming, it moves around the cell, collecting all proteins and organelles with a special marker on them. This special marker, called ubiquitin, tells the phagophore which components need to be broken down.

Stage 3: Phagophore formation completes

The membranes then fully form around the proteins and organelles. When this happens, the name of the structure changes from a phagophore to an autophagosome.

Stage 4: Autophagosome

This autophagosome then moves towards a lysosome and fuses with it. A lysosome is an organelle that can be thought of as the stomach of the cell. Although it’s not exactly true, as a cell contains many lysosomes!

Stage 5: Auto Lysome

As in our stomach, lysosomes’ contents are acidic and contain digestive enzymes that break down the proteins and organelles.

Once broken down into individual amino acids, these components are re-used to build new proteins, organelles, and even new cells. Or, they may help with energy production in the liver through a process known as gluconeogenesis.

The mTOR enzyme stimulates the amino acids used for the new cells and proteins.

Therefore, the ‘feast and famine’ cycle completes itself as the body switches between autophagy and mTOR!

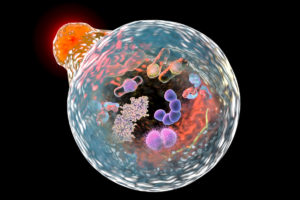

Autophagy in the mitochondria

There is also a specific type of autophagy that deals with mitochondria. This occurs by selective degradation of the mitochondria through a process called mitophagy.

Mitochondria, also organelles, are the engines of our cells and produce our energy. We have large numbers of them in each of our cells, 2000 or more.

However, because we use oxygen to produce energy and oxygen creates oxidative stress, our mitochondria constantly deal with free radicals. This means they are very susceptible to damage. Breaking down and repairing damaged mitochondria is a critical process undertaken in mitophagy.

So, is stimulating Autophagy via intermittent fasting worth it?

Intermittent fasting can have some very positive health benefits:

- It can stimulate autophagy.

- It’s associated with an increased lifespan.

- Also, it can stimulate the production of new mitochondria.

- It can reduce inflammation as well as improve cardiovascular health.

- It helps people lose weight.

- And it can help with reducing high testosterone levels in women.

However, whilst there are some excellent benefits, I haven’t mentioned one potential problem with fasting. And that is, we must make sure we are definitely fasting and not just starving ourselves.

When fasting is done correctly, it shouldn’t be something that produces bad side effects like dizziness, weakness, irritability, or anything else that’s very negative.

It’s OK to feel a bit hungry. However, when you feel bad or think you can’t wait until your eating slot, you’ve initiated a starvation response.

The starvation response happens when we aren’t producing enough ketones to fuel our brains. Instead, because it doesn’t have enough energy coming in as we eat, our brains perceive a dangerous food shortage. It then does everything it can to make us stop doing things and save energy by making us feel lousy.

I have written a detailed guide on how to avoid the starvation response, so please read it before deciding if this is for you.

With the right information and understanding of how intermittent fasting works, most should give it a try and feel all the potential benefits in their health!

💬 Something on your mind? Share your thoughts in the comments. We love hearing from curious minds.

📩 And while you’re here, join our newsletter for more smart stuff (and secret perks)!

References

(1) Alternate-day fasting in nonobese subjects: effects on body weight, body composition, and energy metabolism, Leonie K Heilbronn, Steven R Smith, Corby K Martin, Stephen D Anton, Eric Ravussin, Am J Clin Nutr . 2005 Jan;81(1):69-73.

(2) Intermittent energy restriction improves weight loss efficiency in obese men: the MATADOR study, N M Byrne, A Sainsbury, N A King, A P Hills, R E Wood, Int J Obes (Lond) . 2018 Feb;42(2):129-138.

(3) Effects of caloric restriction on SIRT1 expression and apoptosis of islet beta cells in type 2 diabetic rats, Xiangqun Deng, Jinluo Cheng, Yunping Zhang, Ningxu Li, Lulu Chen, Acta Diabetol . 2010 Dec;47 Suppl 1:177-85.

(4) Is Ramadan Fasting Safe in Type 2 Diabetic Patients in View of the Lack of Significant Effect of Fasting on Clinical and Biochemical Parameters, Blood Pressure, and Glycemic Control? M. M’guil, M.A. Ragala, L. El Guessabi, S. Fellat, A. Chraibi, L. Chebraoui, Clinical and Experimental Hypertension Volume 30, 2008 – Issue 5

(5) The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women, M N Harvie, M Pegington… Int J Obes (Lond) . 2011 May;35(5):714-27.

(6) Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting and caloric restriction on the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems, Mark P Mattson, Ruiqian Wan, J Nutr Biochem . 2005 Mar;16(3):129-37.

(7) Behavioural changes are a major contributing factor in the reduction of sarcopenia in caloric-restricted ageing mice, Klaske van Norren, Fenni Rusli… J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015 Sep; 6(3): 253–268.

(8) Advanced Glycation End Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet, JAIME URIBARRI, MD, SANDRA WOODRUFF, RD, SUSAN GOODMAN, RD, WEIJING CAI, MD, XUE CHEN, MD, RENATA PYZIK, MA, MS, ANGIE YONG, MPH, GARY E. STRIKER, MD, and HELEN VLASSARA, MD, J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 Jul 8.

(9) Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying Health Benefits of Fasting, Stephen D. Anton, Keelin Moehl… Obesity (Silver Spring). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 Apr 30.